Zachary Armstrong: Grids and Abstracts

Apr 30–July 18, 2021

In Zachary Armstrong’s studio, there is a scale model of The Contemporary Dayton’s new gallery space, immaculately rendered with minuscule versions of his paintings, drawings, objects, and wallpaper that will fill the new space at the Dayton Arcade. It is an intensely dense and visually concentrated microcosm, especially when viewed at eye level, crouched down next to the model. Standing up, one’s view becomes wider, airier, and grander. The paintings in the studio (those in Grids & Abstracts and those intended for other destinations) fill the eyes and take up every possible space. Canvases lean three deep against the walls, tables support those in process.

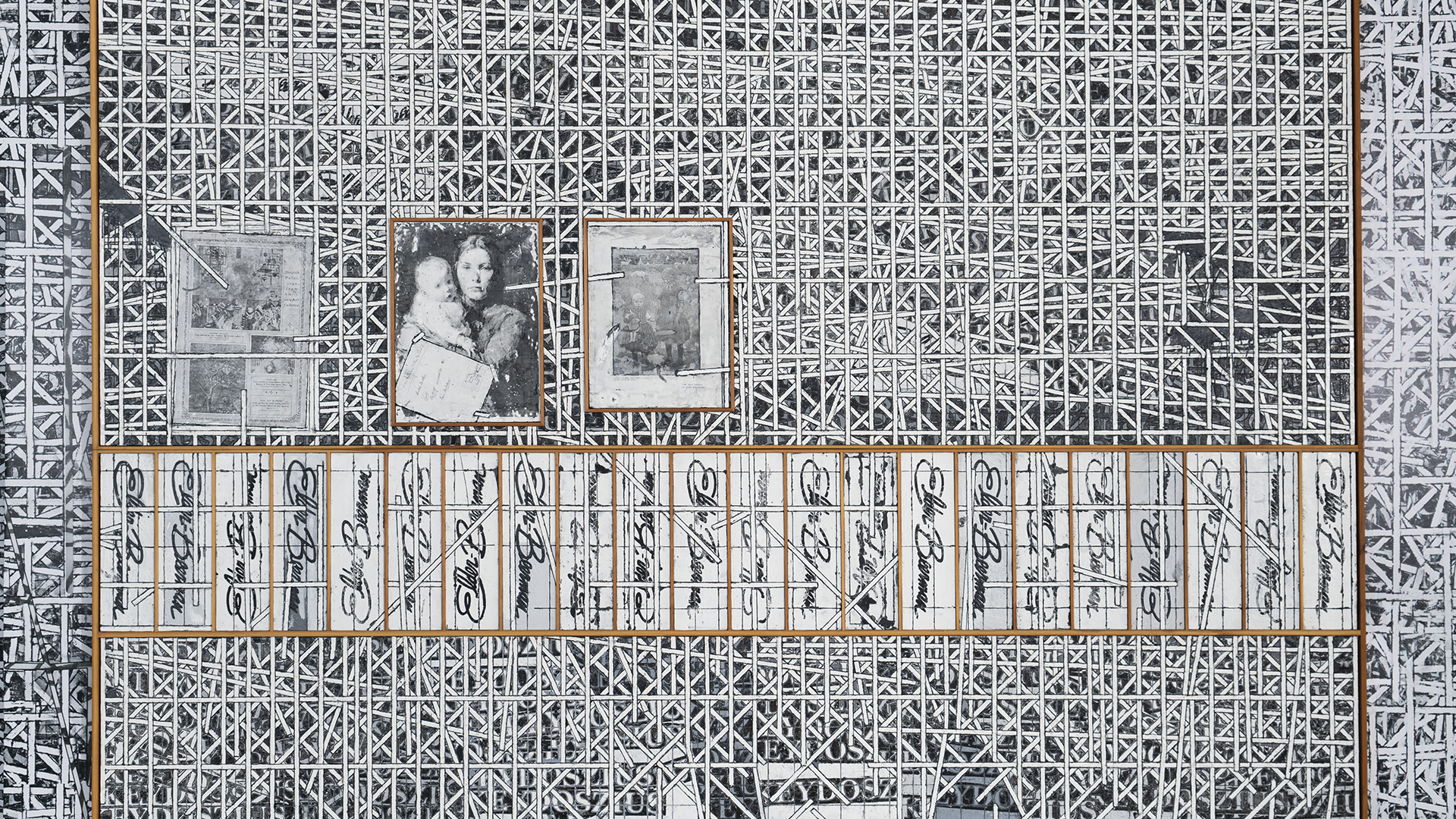

With time and across the studio, an observer comes to recognize an interconnectedness at play. There is comforting repetition amongst the measured cacophony. There is regularity here, determined by the persistent multiplication of an iconographic store of treasured and essential images: childhood line drawings, the Elder Beerman logo–drawn from the now-defunct local department store–lettering spelling out Armstrong’s mother’s maiden name, Keydoszius, and a Gari Melchers Mother and Child painting from c. 1906 (in the Art Institute of Chicago collection). These objects are the archival building blocks for a painting project that both yearns for abstraction and recognizes its indebtedness to familiar shapes, beloved people, and well-known places.

Three days after Armstrong was born, his older brother Noah drew him as a stick figure with a cartoonishly oval head. That drawing (and others), copied over and over and over again, has led to a practice that has determined the paintings in this exhibition. Layer upon overlapping layer, these drawings, and accompanying grids are the warp and weft, the framework. Their layering has become a vocabulary while the lines of figurative drawings have widened to bars that glide just slightly off-kilter. Motifs, logos, lettering, lamps, art journal covers, and more of the records and documents of Armstrong’s life, linger amid and among this keyed-up, latticed array so that abstraction and figuration exist simultaneously within the work. The grid and the line hold the depicted objects at the surface and allow them to function like Jasper Johns’ Flags–both immediately recognizable and part of an overall treatment of the canvas as an enmeshed ecstasy of paint and texture.

Abstraction is not always about abandoning the things that link us to the world. In fact, for Armstrong, his imagery, lettering, and signage remain essentially formative even as they slip through encaustic paint into something more akin to overall pattern. Form is always there, always relied upon as a kind of alpha and omega, a purposeful and constant hold on the things that matter, a mother tongue, a structure that guides and caresses memories while also disintegrating at the edges. It helps that his material is such a thick and mucky stuff. Get up close to any square inch of a painting and look at it for a while. Like the tache that build up the special architectural volumes of Cezanne’s apples, Armstrong’s waxy accumulations are messy and gestural and the building blocks of form. Compare them too with the painted and copied moments within Robert Rauschenberg’s combines and screenprint paintings and there is a similarity in the way things appear again and again, demanding our attention to their literal and symbolic qualities. Leo Steinberg described this part of Rauschenberg’s efforts as a “kind of optical noise,” and it seems an apt description of what is happening here.”

Part of the pleasure culled from the optical noise emanating from the canvases is the way one can be broadsided by their novelty while also drawn into an art historical genealogy. The encaustic and the collage, the repetition, and the readymade lead to connections with

Robert Rauchenberg, Robert Gober, Edouard Vuillard, Marcel Duchamp, and Jasper Johns. Conversations with the artist extend connections to include Brice Marden, Pablo Picasso, Andrew Wyeth, Paul Cezanne, Nancy Graves, Grant Wood, and Gari Melchers. There is equal enthusiasm recounting working in the studio of Curtis Barnes, Sr.—the great Dayton painter and educator who was an early mentor and eventual friend of Armstrong’s—and discussing his emotional relationship to Jack Tilton, who first visited Dayton in 2015. Sit down with Armstrong for any amount of time and the juiciest conversations about these or others will lead him to grab an exhibition catalogue, open a sketchbook, scroll through photographs, or leaf through stacks of images collected and serving as tools in a workhouse churned by sheer will to make things out of his archival matrix of information.

Wallpaper appeared again at The Wexner Center’s Inherent Structure, a group show of contemporary abstraction in 2018 where the lobby wall disappeared into a wild organization of grid lines and repeated Noah figures playing atmospheric discombobulation to a pair of paintings floating above but inseparable from the rest. The wooden line of the excellently and sparely crafted frames the only marker of difference.

At The Contemporary Dayton, wallpaper covers almost every square inch of the gallery and is both a continuation of the paintings and the recipient of every bit as much attention as the canvases. In fact, the process of designing and placing the wallpaper was carefully considered, developed, and adapted over months. The Noah drawing is there, the grid and bars are there, and even the paintings are copied there–repeated in their totality and positioned nearby, allowing reiteration to become a necessary and welcome part of the activity of looking. The letters, logos, and lamps reprise their roles but slide from canvas to wall, insistently asserting themselves as foundational imagery while also playfully reckoning with the imitative decorativeness inherent in covering walls with patterned paper. The all-over effect is unrelenting, bracingly tough, and embracingly detailed.a

Grids & Abstracts is both a unified work surface, a plane where everything is of equal import, a space which has received Armstrong’s thorough attention, and a palimpsest where accumulated information offers itself up to be combed through, recognized, and remembered over and over and over again.

Sponsors

Exhibition Sponsor

Stene Projects, Stockholm

Programs

Dr. Robert L. Brandt, Jr.